Evanston, Ill., has made history. It recently voted to give reparations to its African-American residents. That makes the city the first of its kind to take financial responsibility for the suffering that’s resulted from slavery and an era of segregation.

The Vote

The Evanston City Council voted in the positive to initiate the first phase of the $10 million, 10-year Restorative Housing Reparations. The commitment to black residents will see payments for discriminatory housing practices between 1919 and 1969.

This phase constitutes $400,000 to be dispersed in increments of $25,000 for mortgage assistance or home improvements. The program will generate funds through a three percent tax on the sale of recreational marijuana.

Qualifications for the reparation entail applications having lived in Evanston during the 1919–1969 period or have descended from a resident who did. There will be random selections of recipients if more applicants than funds complicate matters.

The Voices

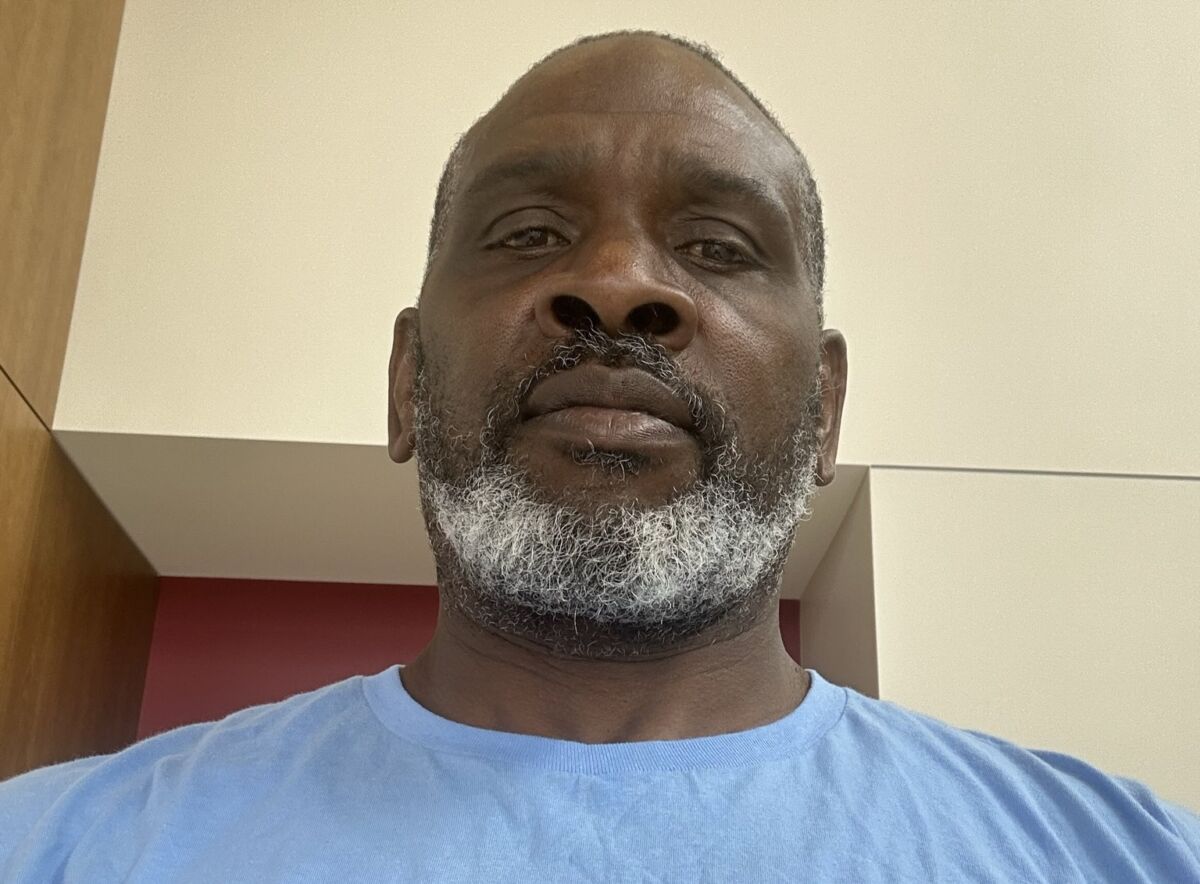

Alderman Robin Simmons first presented the reparations plan in February 2019. “It is the reckoning. We’re really proud as a city to be leading the nation toward repair and justice.”

One dissenting voice and vote for the plan came from Alderman Cicely Fleming. Not because she’s against the program. She has been critical of the program’s scope, arguing it doesn’t go far enough. She says, at this time, the plan is nothing more than “a housing plan dressed up as reparations.

“We must understand the definition of true reparations and its main goal: to do that, the People dictate its terms to Power, not the other way around. Rather, this resolution is dictating to Black residents what they need and how they will receive what they need.”

Alderwoman Robin Rue Simmons is another architect of the reparations program. She’s stated the program is designed to solve two major issues plaguing the community. The first is addressing the disproportionate arrests black residents suffered for minor infractions involving marijuana possession. The second is the history of blacks being unfairly treated by the real estate market.

Using historical evidence, the plan’s advocates established a clear link between the suffering and the city’s actions.

The History

The BIPOC community have long been victims of the real estateindustry. It zoned the market ensure people of color resided in less desired and less developed neighborhood. The city’s banks denied people of color loans for living in better parts of Evanston. If a black person managed to get their hands on a lot, banks denied them loans to build. These landowners were eventually forced to sell the property.

“We have a large and unfortunate gap in wealth, opportunity, education, even life expectancy,” Alderman Simmons attests. It’s led her and her colleagues to “pursue a very radical solution to a problem that we have not been able to solve: reparations.”

A number of towns and cities in the United States are preparing or considering similar ordinances. With Evanston’s heroic program in place, the city’s program is expected to be a model that all other municipalities will use.